Beginning this month, Rereeti kickstarts an online initiative aimed at highlighting objects of art, collections and pieces of obscurity from museums and institutional collections across India that the public should know more about. This month, we feature five artifacts from the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai.

History of CSMVS

In 1904, some leading citizens of Bombay decided to create a museum to commemorate the visit of the Prince of Wales (later King George V). The Governor of Bombay provided a semi-circular plot of land in the heart of the city aptly called the ‘Crescent Site’ with the condition that the citizens of Bombay create an autonomous body and undertake the responsibility of running the museum. The foundation stone of the museum was laid by the Prince of Wales on November 11, 1905 and the museum was named “Prince of Wales Museum of Western India”.

The museum was finally established with public contribution and aided by the then Government of Bombay Presidency. Following an open design competition, the British architect George Wittet was commissioned to design the Museum building in 1909. Designed in the Indo-Saracenic style, the monumental edifice is a combination of Hindu and Saracenic architectural forms with some elements of Western architecture, with a big dome at the centre, two smaller domes on either side and complimented by a beautifully laid garden. Wittet was inspired by the huge dome of Gol Gumbaz in Bijapur and its inner vaulting arches which he carefully incorporated in the interior of the museum building. The beautiful octagonal wooden arched pavilion which was artistically added in the central foyer was originally a part of an 18th century Wada (a Maratha Mansion) located near Nashik.

The construction of the building was completed in 1914, but was initially used as a Children’s Welfare Centre and a Military Hospital during the First World War and was formally opened to the public as a museum on January 10, 1922 by Lady Lloyd, the wife of George Lloyd, Governor of Bombay.

The museum building is deemed as a Grade I heritage building of the city and was awarded the first prize, ‘Urban Heritage Award’ by the Bombay Chapter of Indian Heritage Society for heritage building maintenance in 1990 and was recently awarded the ‘UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation’ by the UNESCO Culture Unit, Bangkok.

CSMVS houses more than 60,000 artifacts and has an outstanding collection comprising sculptures, terracotta’s, bronzes, excavated artifacts from the Harappan sites, Indian miniature paintings, European paintings, porcelain and ivories from China and Japan, etc. Besides these, the Museum has a separate natural history section which is a major attraction for children. The museum welcomes more than a million visitors every year.

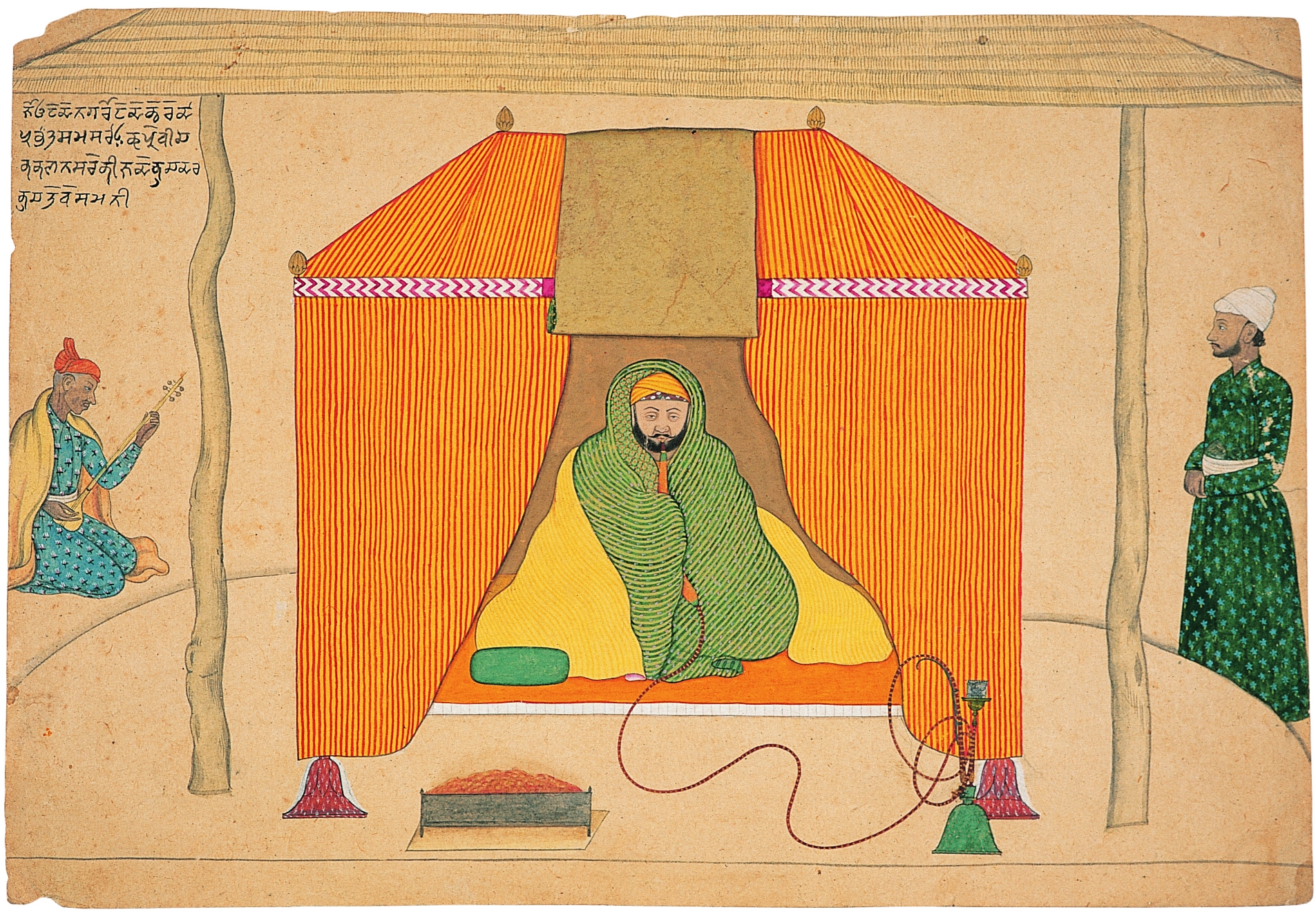

Image: Balwant Singh in a Tent at Nagrota, Pahari, Jammu; attributed to artist Nainsukh, circa 1760 CE.

This painting by the artist Nainsukh, was done under the patronage of Balwant Singh. It offers interesting material for the study of the transformation of the rustic vibrancy of the early Pahari style to the sophisticated and lyrical style of Guler and Kangra painting.

The painting shows Balwant Singh at the base camp at Nagrota. He is resting in a temporary shelter after a march. A green shawl and a blanket wrapped around him and a small fire altar in front indicate the cold weather. The Raja smokes a huqqa while a musician plays a stringed instrument which looks like a local version of the rabab. On his left an attendant stands with folded hands. All three have grim expressions.

Nainsukh was a master of line and his figures comes alive, in full flesh, with just a few deftly drawn lines. He introduces dimensions to flat figures by a slight shading along the borders that separate the figures form the background or from other figures. This shading can also be seen around the neck, below the chin and around the collars of the jamas. Minute details along with accurate depiction of posture create a convincing naturalism essential for portraiture which Nainsukh extensively explored under the patronage of Raja Balwant Singh. Out of the 65 paintings that have been ascribed to Nainsukh so far, the museum houses 17, making it the single largest collection of Balwant Singh’s paintings by Nainsukh.

Image: Devotee, terracotta; Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan; 5th century CE.

This sculpture is the legacy of the famous 19th Century archaeologist Henry Cousens who excavated the site of a stupa at Mirpurkhas, one of the most important and well preserved sites of the Indo-Greek Buddhist settlements. This terracotta was found leaning against the north wall of the central shrine. Curiously, this the only secular image among the large number of religious figures found at the site. The image probably represents a donor disciple who contributed towards the construction of the stupa.

The modeling is a bit heavy, but the expressive face, particularly the half-closed thoughtful eyes, the sharp arch of the eyebrows and the full lips impart an unusual charm to the figure. Look how the hair arranged with care. The ear ornaments do not match each other: the left earring is larger and has three pearl drops. Possibly this special earring indicates a position of office. (A similar custom in Tibet was prevalent till the 18th Century where high officials in the government wore a special kind of earring in one ear.) The elaborate hairdo also seems to be a mark of an important position in the state administration.

The devotee’s elegantly-draped striped dhoti (lower garment) has traces of paint. The manner in which he holds the flower is reminiscent of the famous painting, Bodhisattva Padmapani, in Cave No. 1 at Ajanta.

Image: Great Hornbill, Buceros bocornis.

The Great Hornbill is the largest member of hornbill family. It is found in the dense evergreen and moist-deciduous forests of the Western Ghats from Maharashtra to Kerala, the Himalayas, from Uttarakhand to Arunachal Pradesh, and Andaman Islands.

The Hornbill is a large bird. The most prominent feature is the bright yellow and black casque on top of his massive bill. The female hornbill is smaller than the male. Hornbills are remarkable for their extraordinary breeding habits. The pair chooses a suitable hole in a tree for nesting. The female enters it and the hole is sealed by the male, leaving only a little opening for feeding and air. She remains imprisoned in her nest until the chicks are half grown. Relying on the male to bring her food. The clutch consists one or two eggs which she incubates for 38-40 days.

Hornbill pair bond for many years and in some cases, for its entire lifetime. They are mostly seen in pairs and in groups up to 30. Its diet mainly consists of fruit. But it will also eat small mammals, birds, lizards, snakes and insects.

The male bird on display here was named William, a pet of the Bombay Natural History Society. It lived on the society premises nearby for 26 years and died in 1920. The population of Great Hornbill declined, possibly due to poaching for food and for its casque used as a head dress by local tribes. Great Hornbill is endangered and protected under Wildlife Protection Act, (1972) of India.

Image: Rewa Dagger; Jade; Former Rewa State, Madhya Pradesh; late 17th century CE.

The bejeweled dagger, a prized possession of nobility, was often worn ceremonially and was a sign of statue at the durbar. Such daggers were not merely ceremonial, but served as real weapon for defense and attack in close combat. If you look at the blade, it is made of high quality watered steel and can be lethal.

The pommel of the hit is studded with rubies, emeralds and diamonds forming a rose and creeper pattern on both the side. On either side of the quillon, there is a multi-petalled rose, studded with rubies and a diamond in the centre. The scabbard is covered with a pink silk brocade and a decorative cape and locket to match the hilt. The tassels at the end are made of a bell-shaped, studded jade piece with loop of seed pearls. This dagger once belonged to the royal family of Rewa in Madhya Pradesh. You can see such bejeweled daggers tucked in the sash or waistband of royalty in many miniature paintings.

Image: The Sword of Damocles (1804), Antoine Dubost (1769 – 1825); French, oil on canvas.

The theme of the painting is a variant form of the proverb ‘judge no one happy until his life is over’. It revolves around a sword, a metaphor of never ending threat, and the protagonist, Damocles.

Damocles is a flatterer courtier of Dionysus the Elder of the 4th century B.C. tyrant king of Syracuse. Dionysus asks Damocles whether he would he like to try out Dionysus’ life. Damocles readily agrees. Damocles enjoys everything immensely until he notices a sharp sword hovering over his head that is hanging from the ceiling by a strand of horsehair. This, the tyrant explains to Damocles, is what life as ruler is really like.

Rendered in the Neo-Classical style prevalent in the 19th century CE, this history painting shows Damocles reclining on a golden couch, surrounded with luxuries and attractive servants. Above his head is the suspended sword at which he is gazing with apparent horror.

Antoine Dubost was a French artist who studied at the École des Beaux Arts. ‘The Sword of Damocles’ was exhibited in 1804 in an exhibition at the Leicester Square, London. Dubost received a gold medal from Napoleon and the coveted praise of Jacques Louis David, the great master of Neo-Classicism.

Thomas Hope, a Dutch and British merchant banker, author, philosopher and art collector, purchased the painting. Hope chopped off some part of the painting along its top and bottom edge in order to accommodate it into a symmetrical hang in his home, altered the position of the sword from perpendicular to diagonal, replaced the horsehair with a knot and, on top of everything, influenced by Dubost’s critics, doubted his ability as an artist of a creation of such a masterly quality and effaced his signature.

In 2006, the cleaning of the canvas was undertaken by the Museum’s conservation department which uncovered the artist’s signature inscribed on the footstool, partially in Greek: ‘ΔUBOST EΠOIEI’ meaning ‘Dubost made it,’ which is now clearly visible. The original sword, which now appears short, is also visible through the overpaint.

Would your museum like to be part of this monthly initiative? Please send us images and a brief description of five objects from your collection that the public and our readers should know more about. Write to marketing@rereeti.org.

Really liked this initiative. Are the objects shared by the museum’s team or picked by Rereeti?

Some information on that and some external links would be great.

Good to see Indian museums are opening up like this. There is hope yet!! 🙂

Thank you Ambika. Mostly shared by the museum’s team.