Deepthi Radhakrishnan explores how living heritage spaces can act as platforms for learning, creativity and heritage management for visitors and the organisation.

Image: The hoisting of the Tibetan Prayer flags is to ensure good fortune and well-being. It is one of the many customs within the nomadic communities of Tibet that have changed very little for several thousand years. Prayers are carried on the wind, and in Tibet, the prayer flag is known as the ‘wind-horse’. Photographs credit: Rishi S.

The Norbulingka Institute was established in 1988, to keep alive centuries old Tibetan traditions in content, form and process by providing apprenticeships in traditional Tibetan art forms and making Tibetan experience accessible for contemporary lifestyle.

Upon a trip to McLeodGanj (Himachal Pradesh) late last year, a dear friend suggested a visit to the Norbulingka Institute. Where previous trips to the Himachal had not provided me with an opportunity to visit the place, I pursued the idea with a zest and fervour formerly unclaimed. It was about a 40 minute bus journey from McLeodGanj, with pleasant weather to cheer me on. I alighted at the Sacred Heart School, Sidhpur bus stop and was directed toward an ascending road and uphill hike of about 1.5 km. Only a moody drizzle could add that touch of magic to an unknown destination of great repute for its Zen beauty and a Shangri-La like embodiment. The mundane and everydayness of the views leading up to the Institute further accentuated the awe that I felt when I walked into Norbulingka the first time.

To me, the Institute is a reminder of the complex societies that we are as a country. I am inclined to agree with Appadurai and Brekenridge1 when they suggest the striking facts about complex societies such as India and how we have not surrendered learning principally to the formal institutions of schooling. Since the upper middle class tend to control the colleges and universities and urban groups tend to monopolize post-secondary schooling, learning, is therefore often tied to practical apprenticeship and informal socialization. Also, and not coincidentally, these are societies in which history and heritage are not yet parts of a bygone era that is institutionalized – and historicised – in history books and museums.[1]

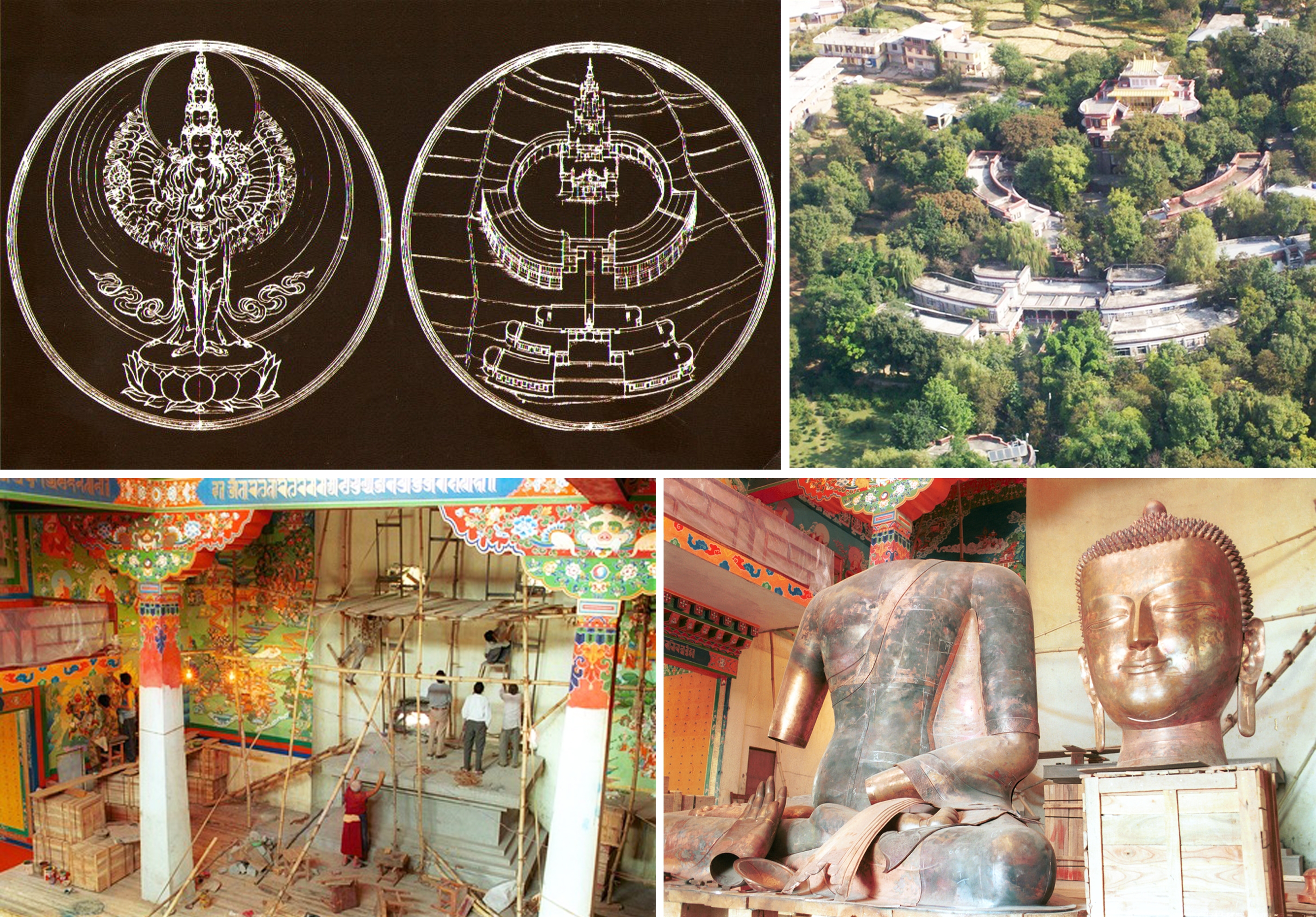

Image: The ground plan was designed to follow the proportions of Avalokitesvara, the deity of compassion. The workshops and offices were to be constructed in the shape of his thousand arms. The temple would be his head, while in the middle would be a water spring, representing his heart, emanating kindness to all living beings. Photographs credit: the Norbulingka Institute

One such effort towards the revival, preservation and adherence to traditional crafts was born from the shared vision of Kelsang Yeshi (Minister of the Department of Religion and Culture) and his wife Kim Yeshi who imagined an institute in India that could act as a cradle for the revival of Tibetan art, and provide a haven for artists to practice their crafts. The Norbulingka Institute was established in 1988, to keep alive centuries old Tibetan traditions in content, form and process by providing apprenticeships in traditional Tibetan art forms and making Tibetan experience accessible for contemporary lifestyle. This begs to answer a question that one might want to consider, what public needs can history serve?

The Norbulingka Institute derives its name from His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s beautiful summer residence, the ‘Norbulingka’ (Jewel Garden), set in parkland two km from Lhasa. Fearing for the future of Tibet’s cultural heritage, the Seventh Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso, established institutes of arts and science there in 1754. With Tibet occupied, the Norbulingka Institute in Dharamsala has taken the initiative to preserve the roots of Tibetan culture in exile. While this could be viewed as a dialogue-driven Institute, enagaging with and providing a platform for a continued legacy of arts, crafts and religion, personally, this refurbishes Karp’s statement about how public culture provides some relatively formal settings for definitions and experiences of identities. That said, public culture is only one forum in which people experience ‘who’ they are and the sources of power are derived from the capacity of cultural institutions to classify and define peoples and societies. This is the power to represent: to reproduce structures of belief and experience through which cultural differences are understood.[2] Would this raise questions of notions of ‘belonging and ownership’ for Tibetans in India?

As Kim Yeshi states, “The goal of Buddhist practice is the attainment of spiritual realization that frees beings from the bonds of cyclic existence. The purpose of Buddhist art, therefore, is to provide support for that realization by representing objects of meditation that serve as sources of inspiration.”

Every aspect of the Norbulingka Institute reflects this essence with great attention paid to design, meaning and quality. The various segments come together as a seamless whole while maintaining an individual story through its materials, processes and themes.

Temple

Image: The magnificent two stories high Thangka appliqué hanging from the ceiling displays the Buddha and the 16 arhats. Photographs credit: the Norbulingka Institute

Set among the Institute’s delightful Japanese-influenced gardens is the central Deden Tsuglakhang temple. It is a magnificent example of Tibetan religious architecture, imbuing the visitor with a sense of calm and meditativeness. It has on display some of the finest work done by artists in-house —the walls are adorned by thangka frescoes depicting the deeds of the Buddha, the Fourteen Dalai Lamas, and other great Buddhist masters. Hanging from the ceiling is an appliqué thangka, over two stories high, displaying the Buddha and the 16 arhats, a riveting example of craftsmanship and dedication. The temple’s centrepiece, the Buddha Shakyamuni is a 14ft gilded statue, one of the largest of its kind outside Tibet, crafted from hand-hammered copper sheets.

Losel Doll Museum

Image: Photographs credit: the author, Deepthi R

Image: Photographs credit: the author, Deepthi R

Housing a collection of over 150 dolls dressed in traditional costumes from various regions of Tibet, the Losel Doll Museum presents the stories of Tibet and its culture in a well-researched manner. The dolls are displayed in dioramas depicting traditional life. Although in its present state, the museum requires attention to maintenance and better gallery lighting, what presents itself if you look closely, are dolls whose costumes have been made from the same materials, as the originals would have been and showcasing the richness and diversity of life on the Tibetan Plateau. The interpretation is informative.

The Workshops

The Statue-making process — two materials became common in Tibetan statue making: clay and metal. But at the Norbulingka, they work solely with metal. Photographs credit: Julie Hall, Rishi S., the Norbulingka Institute website.

The workshops offer a range of specializations in the various Tibetan art forms — from Thangka painting, Thangka appliqué, statue making, woodcarving, wood painting to tailoring and weaving. Norbulingka offers workshops ranging from one day to several months. Courses are designed based on the time and interest of individuals and groups.

Photographs credit: the Norbulingka Institute website, Julie Hall and the author

Photographs credit: the Norbulingka Institute website, Julie Hall and the author

Shop

Norbulingka’s shop offers the centre’s expensive but beautiful craftworks and a complete range of products — from thangkas to hand-carved furniture to Norbulingka’s soft and elegant line of clothing. The quality of the materials and craftsmanship is unmatchable, with products primarily targeted at an elite, niche & foreign audience.

Hummingbird Café

Image: Amidst the beautiful Zen gardens of Norbulingka is the Hummingbird Café that serves vegetarian meals and snacks. Photographs credit for Shop & cafe: the Norbulingka Institute

Image: Amidst the beautiful Zen gardens of Norbulingka is the Hummingbird Café that serves vegetarian meals and snacks. Photographs credit for Shop & cafe: the Norbulingka Institute

The Institute also houses a stylish Norling House offering comfortable rooms decorated with Buddhist murals and handicrafts from the Institute, around a sunny atrium. A short walk outside the complex is the large Dolmaling Buddhist nunnery.

The Norbulingka Institute presents a sustainable business model for any community that is looking to keep alive traditions and make experiences accessible for a contemporary lifestyle. It works with a strong social mission: keeping Tibetan culture alive by training people for the future.

[1] Appadurai, A., Brekenridge, Carol A. “Museums and Communities — The Politics of Public Culture.” Museums are Good to Think: Heritage on View in India.

[2] Karp, Ivan. On Civil Society and Social Identity

About the Author

Deepthi Radhakrishnan is Rereeti’s Education & Design Officer. She holds a graduate degree in design (NID, India) and master’s degree in Museum Studies (UEA, UK). She was the recipient of the Education Fellowship at the Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts (SCVA, UK). She is passionate about illustrating and designing outreach programs for museum visitors. Get in touch with Deepthi.

Deepthi Radhakrishnan is Rereeti’s Education & Design Officer. She holds a graduate degree in design (NID, India) and master’s degree in Museum Studies (UEA, UK). She was the recipient of the Education Fellowship at the Sainsbury Center for Visual Arts (SCVA, UK). She is passionate about illustrating and designing outreach programs for museum visitors. Get in touch with Deepthi.

Well, the article is well worth to read.

Gaggal airport taxi service