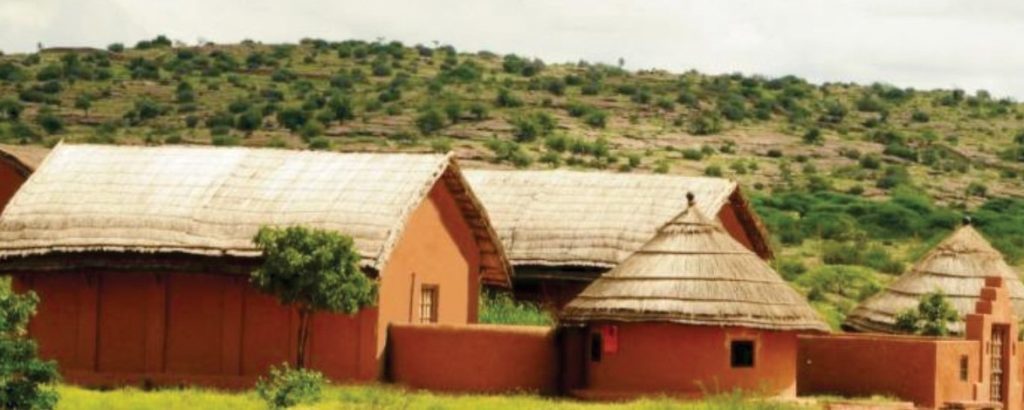

The words Arna-Jharna literally mean ‘forest spring’. On one hand, it would seem to be an appropriate name for a museum devoted to the study of traditional knowledge systems within a larger ecology. Arna-Jharna also happens to be the local name of the region surrounding the museum, which is located 23 kilometres outside Jodhpur city in the semi-arid zone of the northwestern state of Rajasthan in India. If you visit Arna-Jharna, you would find a harsh and stony landscape marked by cavernous sandstone mines and waste deposits. The attempt to create a museum closely linked with the preservation of natural resources in the heart of the countryside is, therefore, a direct response to the larger neglect, if not violation, of the environment. As an experimental venture, whose infrastructure was first initiated around 2002, the museum can be more accurately viewed as an extension of a large body of grassroots research on traditional knowledge going back to the early 1960s.

TJ – Could you tell us the evolution of the museum from a collector’s passion of preserving folk culture to a community space? What does it house?

KK – It was back in 1960 my father Padma Bhushan Late Komal Kothari and his friend Padma Shri Late Vijaydan Detha founded Rupayan Sansthan with the purpose of exploring and understanding the human effort involved in sustaining life based on the utilization of natural resources from immediate surroundings to developing creative or productive social institutions. Both of them (one was an ethnomusicologist and folklorist while the other was a noted author of folk tales) understood the importance of folk life and its sustainability. It started with the collection or oral traditions of the people of Rajasthan. The archive of folk tales and folk songs provided rich content for folklore, ethnomusicology and social history.

This rich archival base come together in the building of a desert museum – Arna Jharna in 2009 . The museum is built on 10 acres of picturesque landscape, 23 km outside Jodhpur. The word “Arna-Jharna” literally means ‘Forest-Spring’. It brings biodiversity, history and culture into one place where contemporary is merged with traditional knowledge systems. The museum is based on two principles –

- the museum as a laboratory of the ordinary, a testing ground of all those basic structures of life that facilitate the art of survival in the desert.

- The museum celebrates the fact that the ‘folk’ is contemporary. The so-called ‘traditional communities’ holding on to skills and modes of knowledge from earlier times are also part of a dynamic, changing present.

TJ -Which are the two most important projects or exhibitions which are important to the museum and why? How would you measure it’s success?

KK – One of the most important projects was the broom project. It was one of the first projects undertaken by the museum after its opening and lasted for three years. Emphasis was not on the panoramic display of hundreds of brooms from the far corners of Rajasthan. Instead, the focus was on the interrelationships of the broom to a wide variety of contexts. From natural resources, local modes of broom-making, the lives of broom-makers from marginalized caste groups, the myths, beliefs, and symbols surrounding the broom, and the economy of the broom. Through this project we were able to develop an understanding of the relationship between the biodiversity of the desert and the lives of people inhabiting and surviving its harsh, yet nurturing, environment.

The second most important project cum exhibition was on folk musical instrument of Rajasthan. The exhibition showcased the oldest and rarest collection of folk musical instruments (Aerophones, Chordophones, Idiophones, Membranophones) and its audiovisual archival material. The project looked at many questions regarding society, culture, caste system and inbuilt capacity of social organization to keep the tradition going, on one hand, and musicological problems like history of the instruments, musical experience, development, diffusion and impact of instruments in determining the peculiar styles of vocal rendering, on the other.

TJ- What are the challenges which the museum/institution/centre faced and how did you overcome them?

KK– While the idea of ‘community’ often suggests social cohesiveness, which is more often than not idealized rather than real, it cannot be separated from a larger spectrum of problems relating to patriarchy and gender which tend to be glossed over by communitarian thinkers. Inevitably, the museum in its initial year faced the realities of caste, which continue to deeply define communities in rural India. The state of Rajasthan, in particular, is known for its dense affirmation of specific caste identities and hierarchies, which are not easily negotiable. For this reason the widespread Harijan community in the state, whose members are employed by local municipalities as sweepers, are still identified as Harijans, and not as dalits. Dalit is the political category which has been mobilized and politicized around the so-called ‘untouchables’ in many states of India. In contrast, the dalit movement has yet to challenge the feudal social structures of Rajasthan, even as the politics around reservations (quotas) for low-caste groups has gained momentum.

The other challenges we faced were in funding, infrastructure and conservation of objects fragile in nature. Some of these challenges exists even today. It has been our observation that the State and Central Government in India are always inactive in promoting institutional and community museums. We are largely raising funds from entry fee, small grants from cultural institutions and sale of publication. Funding bodies like the Ford Foundation has been a major financial support to Rupayan Sansthan for digitization and Broom Project.

TJ- What are the best practices followed by the museum/institution/centre and how did it benefit the organization and the community at large?

KK -The Arna-Jharna Museum acknowledges the diversity of communities and the viability of communitarian structures and forms of knowledge; to this extent, it can be described as a ‘community museum’ . It does not emphasize on any single or specific community. Hence participation and involvement of these various and divergent communities is incorporated in every project and area the museum works on. It has always been our endeavor that the research and documentation of oral history and traditional knowledge systems proves helpful not only for the occupational caste communities but the rural and urban populace as well.

The museum acknowledges that it has a larger ‘developmental’ role to play. In each project we undertake we identify areas and issues that need to be addressed. In the broom project a major issue that was addressed was the stigmatization through caste and poverty that the broom makers experience and the perception other communities have of them. Health hazards resulting from broom production, the relative absence of education among the children of broom-making communities, and widespread alcoholism are among some of the issues identified in the dialogues with broom-makers. Some attempts at introducing governmental schemes of micro-credit were introduced by the staff of the Arna-Jharna Museum to the more entrepreneurial broom-making families of the Koli community. However, after an initial positive response, obstacles were placed by traditional money-lenders in the community who stand to lose from the new developments. It is clear from such setbacks that the road to development is a long and arduous one, and that it necessitates ceaseless dialogue and interaction with the communities concerned.

TJ- What role do you see the museum playing in the lives of the community in the coming years?

KK – An inclusive museum is the way forward. It is important for museums to be a part of the live of the community it serves. The broom exhibition itself was a big perception and change of mindset of the people both in urban and rural areas to visit the museum. We believe there is hardly anyone who doesn’t know the broom and its importance in this region. We strongly believe that if the object belongs to common man then their involvement will develop and make the space sustainable.

In the years to come, we want to build a strong and large community around the museum—a process which is already at work through its long-term association with folk musicians from the Langa and Manganiar communities, who are regular performers on the site of Arna-Jharna. There are also a growing number of professionals like botanists, geologists, scientists, and development workers who are interested in engaging with traditional knowledge systems.

Mr. Kuldeep Kothari, Secretary, Rupayan Sansthan, is an informal but structured communicator on culture and traditions, collecting/archiving/preserving and disseminating audiovisual material related to folk performing arts of Rajasthan. He regularly organizes folk performances at international and national levels to support professional hereditary caste musician communities of the Indian desert state of Rajasthan. Also playing an instrumental role in establishing an ethnographic museum Arna Jharna – The Desert Museum of Rajasthan.

Mr. Kuldeep Kothari, Secretary, Rupayan Sansthan, is an informal but structured communicator on culture and traditions, collecting/archiving/preserving and disseminating audiovisual material related to folk performing arts of Rajasthan. He regularly organizes folk performances at international and national levels to support professional hereditary caste musician communities of the Indian desert state of Rajasthan. Also playing an instrumental role in establishing an ethnographic museum Arna Jharna – The Desert Museum of Rajasthan.

Recent Comments