The Arts Education programme is one of the oldest grant making programmes at the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA). For the first decade of its existence, the programme made a series of wide-ranging grants on a national scale to artists seeking to promote the arts in the classroom. ReReeti spoke to IFA’s Head of Arts Education, Krishnamurthy T.N., to learn more about the initiative’s successes and the road ahead.

ReReeti: What’s the research underpinning the genesis of the Arts Education programme? Did you find a lacuna in the existing teaching pedagogy or curricula? What were some of the urgent issues that needed addressing in 2008?

Krishnamurthy: When IFA initiated its Arts Education programme, the field itself was nascent and offered few coherent examples of effective approaches and strategies. As a response to this lacuna, IFA’s first ten years were shaped around the objective of sparking off a wide range of interventions, strategic grants, as well as collaboration with governmental, non-governmental and arts-based institutions, and support for individuals working with arts education projects.

The first programme indicated interest in a diversity of approaches and outcomes, such as researching and documenting policies and practices in arts education; capacity building for art teachers/faculty working within institutions; arts education resource/materials development; creating networks and exchange between practitioners; and non-formal, community-based arts education projects. It is important to note that IFA experimented with both ideas within arts education, “arts in education” and “education in the arts” in the early phase. While the latter strand, which supported training of aspiring artists within art institutions, had a very short run at IFA (something that will be touched upon a bit later), the bulk of grantmaking up till the present moment has confined itself to arts in education.

Image: “It is important to note that IFA experimented with both ideas within arts education, “arts in education” and “education in the arts” in the early phase,” says Krishnamurthy.

ReReeti: What did the Arts Education programme aim to accomplish? Does this programme cover the whole of Karnataka? What are some of the pedagogic models that inspire your work?

Krishnamurthy: After ten years of wide-ranging grant making within the national circuit, Kali-Kalisu, with its exclusive focus on the government school teacher in Karnataka marks a shift in both the philosophy and practice of arts education for IFA. Kali-Kalisu is a multidimensional project, and each of its frames leads to specific questions and challenges. Within the institutional framework of IFA, the project charts a trajectory where it originates as a series of teacher training workshops and brings into its ambit other recommendations of the review, such as capacitating resource centres, sparking off fellowships, and discourse development in the field. Kali-Kalisu is also a culmination of past processes within IFA where it organically relocates past grantees of the programme in a new terrain of the government school system.

From the perspective of the field, Kali-Kalisu signals a productive, if incomplete, engagement between three different groups of the teacher, the artist, and the government. Further, with its own unique vision and methodology that focus on processes rather than outcomes, and expose recipients to a wide range of art forms, the project can also be seen as a critique of the existing approaches to arts education and teacher training, particularly within the government school system.

Broadly speaking, the project has two strands—one that works at the ground-level with government school teachers and artist facilitators in teacher-training and grant making modes, and another, shaped as a public engagement platform for extending discourses and practices of arts education at the national level.

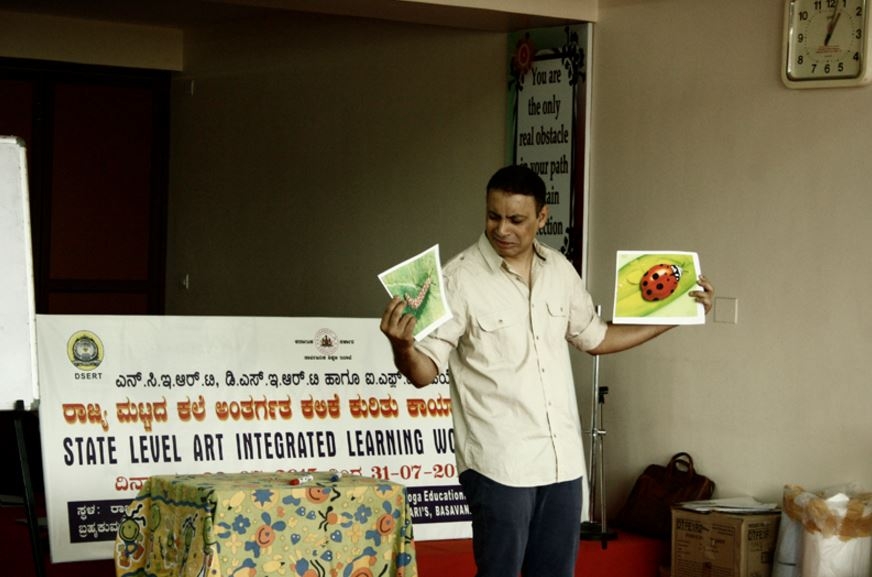

Image: Kali-Kalisu has focused on strengthening the capacities of exemplary teachers from the first year of inception.

ReReeti: How would you describe your partnership with schools? How open have they been in bringing arts education to the classroom?

Krishnamurthy: Kali-Kalisu rolled on in that first year, through seven districts of Karnataka, completing 20 workshops. A total of some 450 teachers came under the programme’s fold, representing a variety of regional contexts and a variety of demographics. In Bidar, for instance, 20 teachers from the Urdu Medium Teachers’ Association were together with 20 teacher trainees of the Carmel Sisters Convent, an occasion of great joy.

In its second year, Kali-Kalisu has focused on strengthening the capacities of exemplary teachers from the first year. They received further training in another series of five workshops over 15 consecutive days, this time at the campus of Nrityagram, the dance academy near Bangalore. New facilitators were brought in to provide different perspectives on arts education. A core team of some 35 teachers were empowered as activists and ambassadors of Kali-Kalisu all across Karnataka. They participated in the two major arts education conferences that Goethe-Institut and India Foundation for the Arts organised in 2009 and 2010. These teachers were positioned to be lead players in a series of regional conferences on arts education.

In its fourth iteration (2012-13), the programme was dominated by the question of sustainability, particularly as funding for the project was coming to a close. To address this issue, two parallel sets of activities were put in place. At the ground level, the Kali Kalisu community was activated through arts education model school grants and support for individual capacity building projects; it was thought that these projects would create a rippling effect on the communities touched by them, and inspire district-wide teachers to the cause of arts education.

Image: Teachers receiving training are positioned to be lead players in a series of regional conferences on arts education.

ReReeti: In the last 8 years, technological proliferation would have changed the face of teaching in the classrooms and outside. Learning is blended and mediated through devices and other audio-visual-creative aids. Has this altered the nature of the proposals you receive? Do you see more inclusive proposals from artists?

Krishnamurthy: No. Our grantee artists are very comfortable in using traditional techniques and they are very much accomplished. But IFA definitely encourage new ideas and initiatives.

ReReeti: Do any of your proposals address arts education for children with disabilities or hearing / visual impairment? If not specifically, what are your thoughts on addressing this?

Krishnamurthy: No. Reason is teachers at many government schools are not well exposed to this. Because art, music and drama classes are based on creative expression teachers have the opportunity to explore creative media in small groups alongside general education peers.

ReReeti: Could you highlight a couple of projects that you found innovative? What were the learning outcomes and how have children and faculty benefited?

Krishnamurthy: The impact of the Kali-Kalisu project is evident in the positive responses. The way Kali-Kalisu has begun its intervention in Arts Education within government school contexts is very crucial and important in the present climate of pedagogy.

The awardee, Mr.Ganapathy Hoblidhar is involved in setting up a cultural group in the village where he teaches as well as hails from. It was impressive to note the way he had positioned the school as a local arts and cultural center. He has built an open air theatre with the aid of the villagers. Workshops and spaces were engaged in conducting Yakshagaana, Janapada mela, music, dance, drawing, clay-modeling, puppetry and similar other activities. A mammoth summer training camp for about 350 children was held from his school, involving the cluster and outsider children. They also have week-end camps with teachers. In this sense Ganapathy, the grantee had meaningfully married SSA program with Kali Kalisu model. Out of 40 teachers, 20 of them hold a meeting every month.

Image: Teachers receive training in storytelling and other creative pedagogical interventions.

Sadanand Baindur intended to take up poetry and through innovative modes, makes the study of poetry an experiential and sensory engagement that brings alive the essence and spirit of poetry. In addition to the poems in the text books in Kannada, Hindi and English which students have to learn, he added a list of poems in Kannada from across the years to give students an exposure to the wide variety and rich language traditions in Kannada.

Kaladhar’s project was to encourage the creativity of the children through writing and book making workshops. ‘Shamanthi’ (meaning chrysanthemum), a recent publication created by his students under his guidance, is a manifestation of the children’s interest in creativity. It received an award from the Shivamogga Kannada Sangha.

A series of art based interventions in the school have helped students to hone their creative skills and visual sensibilities that contributed to the making of the magazine. The short write-ups, stories, plays, cartoons, drawings and poems in the book draw inspiration from everyday experiences of the students. Thus the themes range from agriculture and natural elements to village festivals and local food.

Read about the Arts Education programme initiative on the India Foundation of the Arts website.

About Krishnamurthy T.N.

With a Masters in Art History from Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, Krishnamurthy has served in teaching, policy making, and administration and curriculum development over the last 20 years. He currently heads the Arts Education Programme at India Foundation for the Arts, Bengaluru.

With a Masters in Art History from Karnataka Chitrakala Parishath, Krishnamurthy has served in teaching, policy making, and administration and curriculum development over the last 20 years. He currently heads the Arts Education Programme at India Foundation for the Arts, Bengaluru.

Krishnamurthy T.N. was interviewed via email by Nilofar Shamim Haja.

Recent Comments