‘Tabiyat: Medicine and Healing in India,’ is an upcoming exhibition at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), Mumbai that examines the history and praxis of health in India. Exhibition dates: January 12-March 28, 2016 | Venue: The Premchand Roychand Gallery, CSMVS.

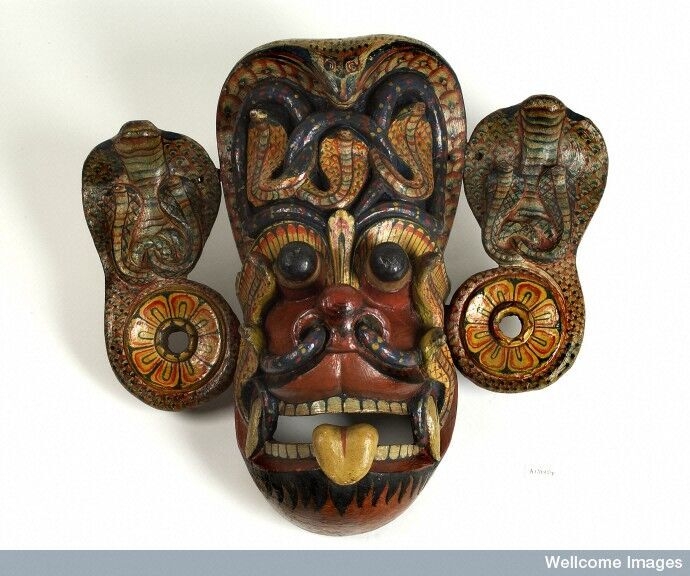

Image: Painted wooden demon mask with cobra-canopied headdress and cobras on lotus disc earpieces, Sri Lanka, probably 19th Century, Science Museum, London.

Rereeti’s Nilofar Shamim Haja spoke to Tabiyat curator Ratan Vaswani, Project Head of Medicine Corner, a multi-city initiative that explores India’s rich plurality of cultures of medicine, healing and well-being through exhibitions, live public events and educational outreach. Tabiyat is the centerpiece of Medicine Corner’s activities in India.

The exhibition is an initiative of London-based Wellcome Collection, a museum that opened in 2007 and houses medical artifacts and original artworks exploring ‘ideas about the connections between medicine, life and art. It is part of the Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation dedicated to improving health.

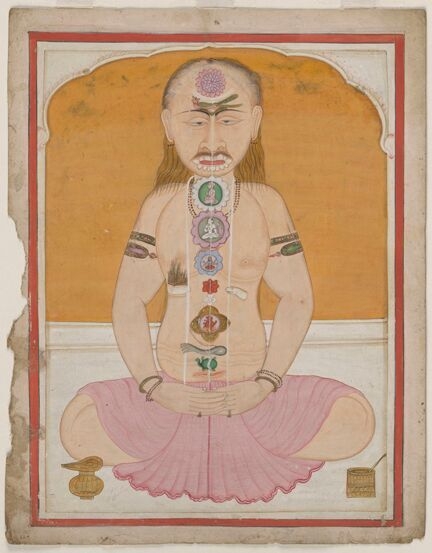

Image: A meditator shown with chakras and kundalini. Unknown artist. 19th Century CE. Wellcome Library, London.

Nilofar: What’s the role of Wellcome Collection in how Tabiyat came together?

Ratan: The Wellcome Collection takes a very broad perspective on health, healing and medicine. It is, for example, a key space for contemporary art. They tend to cover subjects which others may be too squeamish about, such as sex or death. The venue is about understanding the human condition through the prism of medicine and health, but very broadly defined.

The source of the collection is the collecting impulsive of one man, Mr Henry Wellcome, an American in the 1920 and 1930s who founded a pharmaceutical business in London. His great innovation what was then called tabloids and are now called tablets – so medicine in compressed form was invented by Wellcome, he produced them in standard dosage and industrial procedures. He was a great collector and was quite interested in securing objects from around the world, including India, Africa and Asia.

The germ of the idea for Tabiyat came few years ago when Wellcome wanted to work in another country, outside the UK. This has always been a venue for bringing in things outside the country, there have been plenty of exhibits, but what Wellcome wanted to do was something exploratory and innovative for a number reasons: to establish itself as a presence, as an artistic and intellectual project, but also just to investigate how does health work in India. There’s one way to just show a load of historical exhibits or there’s another way, which actually involves visiting India, and curate here. So, this project came out of that idea and I was brought on board to lead it.

“This isn’t just about the objects – it’s about the lived experience.”

Every country in the world has a diversity of medical practices, systems and approaches to healing, health. However, nowhere else on this planet has quite the same riotous diversity and range, plurality of cultures of medicine, health and healing, and of antiquity as India. It made sense to come here as there’s such a range of health practices here related to the economics of the country, the huge cultural differences within the country, it’s old, and modern, it’s full of contrasts.

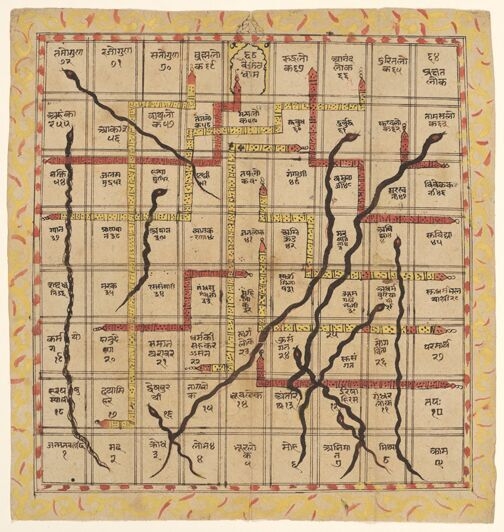

Image: Jnana Bagi (Game of Heaven & Hell); ‘Snakes and Ladders’. Late 18th Century. Wellcome Library, London.

Nilofar: Take us through the curatorial approach and the objects that form part of the exhibition.

Ratan: The key source is the Wellcome Library, which is part of Wellcome Collection and this is the world’s foremost medical library, and it’s not just medical books and manuscripts; it has paintings, all kinds of beautifully illustrated work that you wouldn’t think is related to medicine in any way.

For example, there is a game of snakes and ladders. It is originally an Indian game from the Jain tradition. The snakes represent vices and the ladders represent virtues and it’s used as an aid by parents to teach their children about the virtues of equanimity in both, fortune and misfortune. One of the key aspects of misfortunes in anybody’s life is ill health. In fact, in most people’s lives, historically, illness hasn’t been treatable. Effective medicine, arguably, is quite recent. It’s more about managing ill-health. And the focus has been on how do you handle misfortune, rather than treat the illness itself. So, as far as I am concerned, the snakes and ladders game relates to health, this is why Wellcome Collection has it with them and we are exhibiting this work and others that relate to health.

Image: A pair of wrestlers. Modern facsimile from a 19th century CE Indian album of illustrations. Wellcome Library, London.

There are plenty of things we have commissioned from artists for this show and also sourced it from private collectors and their collections. Some of the objects have also been purchased. For instance, tongue cleaners, which are going to be part of the show. I am particularly pleased about a set of wrestling clubs we have commissioned, historically associated with akhadas or wrestling clubs. The pehelwan or wrestlers, who would suffer shoulder dislocations or other injuries in the course of their sports, learned to treat these amongst themselves. That’s why they are closely associated with the bone setter, who often took on the pehelwan surname.

We wanted to showcase objects like the snakes and ladders game that can be interpreted through the prism of health, but which also have a wonderful aesthetic quality and are a great starting point, intellectually, for delving into the human condition.

There are also select objects from the CSMVS collection, so we have foot scrappers, hair dryers, beautiful objects, but again, quite mundane, and we wanted to provide a spin, a new interpretation to these historical objects. The bulk of exhibits – the spine of the show – comes from London.

Image Gallery: Metal votive offerings. St Mary’s Catholic Basilica, Shivajinagar, Bangalore, 2014; Wax votive offerings. Various Catholic places of worship, Mumbai and South India, 2015; Metal votive offerings at shop near Meenakshi Amman temple, Madurai, 2014; Taveez, Haji Ali Dargah, Mumbai, 2015. All objects acquired for Wellcome Collection, London.

Nilofar: Thematically, Tabiyat is woven around four sections: the home, the shrine, the street, and the clinic. Could you tell us more of this?

Ratan: Tabiyat takes visitors to four generic locations: The Shrine – to encounter the role of spiritual belief in healing; The Home – examining life cycle and the family as the key transmitter of values and practical knowledge for living well and living long; The Street – charting public health, the hidden histories of health commerce and cultural practices such as chewing paan; and The Clinic – treating India as a key site in world history for enquiry into the nature of body and mind and for different analytical models of understanding, representing and treating the body.

When it comes to the four sections, we aren’t thinking of any specific or historical shrine or location or street. This is important to us, because over here (in India), there are sharp boundaries across cultures and people, be it religion, communities and so on. We wanted to surpass those lines. The home in Tabiyat isn’t a Hindu home or a Muslim home or a Christian one, it’s an Indian home and there are common things across those linguistic, cultural and economic divides between people.

History isn’t something that just happened. It’s woven into the fabrics of the viewers lives.

For example, in the Shrine section, there are two kinds of votive objects (made of tin). At St. Mary’s church, you have the wax votives representing parts of the body, so if you got an injured arm, you can buy a wax arm and you place it on the altar, light a candle and say a prayer. There are tin equivalents of those, at the exhibition, which show body parts, and some of them come from Catholic churches in south India and some from Hindu shrines. What’s interesting about them is they are indistinguishable from each other: if you sold them at either of the other venues, you couldn’t tell which is Catholic or Hindu. They probably come from the same press and probably made by the same manufacturer, but used for the same purposes. These are the kind of cross cutting examples that interest me, which I wanted to bring out in the show that this is Indian way of doing something.

The collection has things from across India and all its cultures. There are some documentary photographs from Meghalaya by a photographer who works among the Garo people, which is a scheduled tribe. They are visibly Christianized converts but whose practices are entirely ethnic and follow their ancestors’ rituals and traditions, particularly when it comes to medicine. It’s important to me that the exhibition highlights aspects of the medical traditions in India that are not part of the mainstream (Hindu) practices and the exhibition is inclusive. It’s a very deliberate curatorial approach, and not at all happenstance, to bring in the huge diversity of India. We didn’t want to just do a survey kind of exhibition.

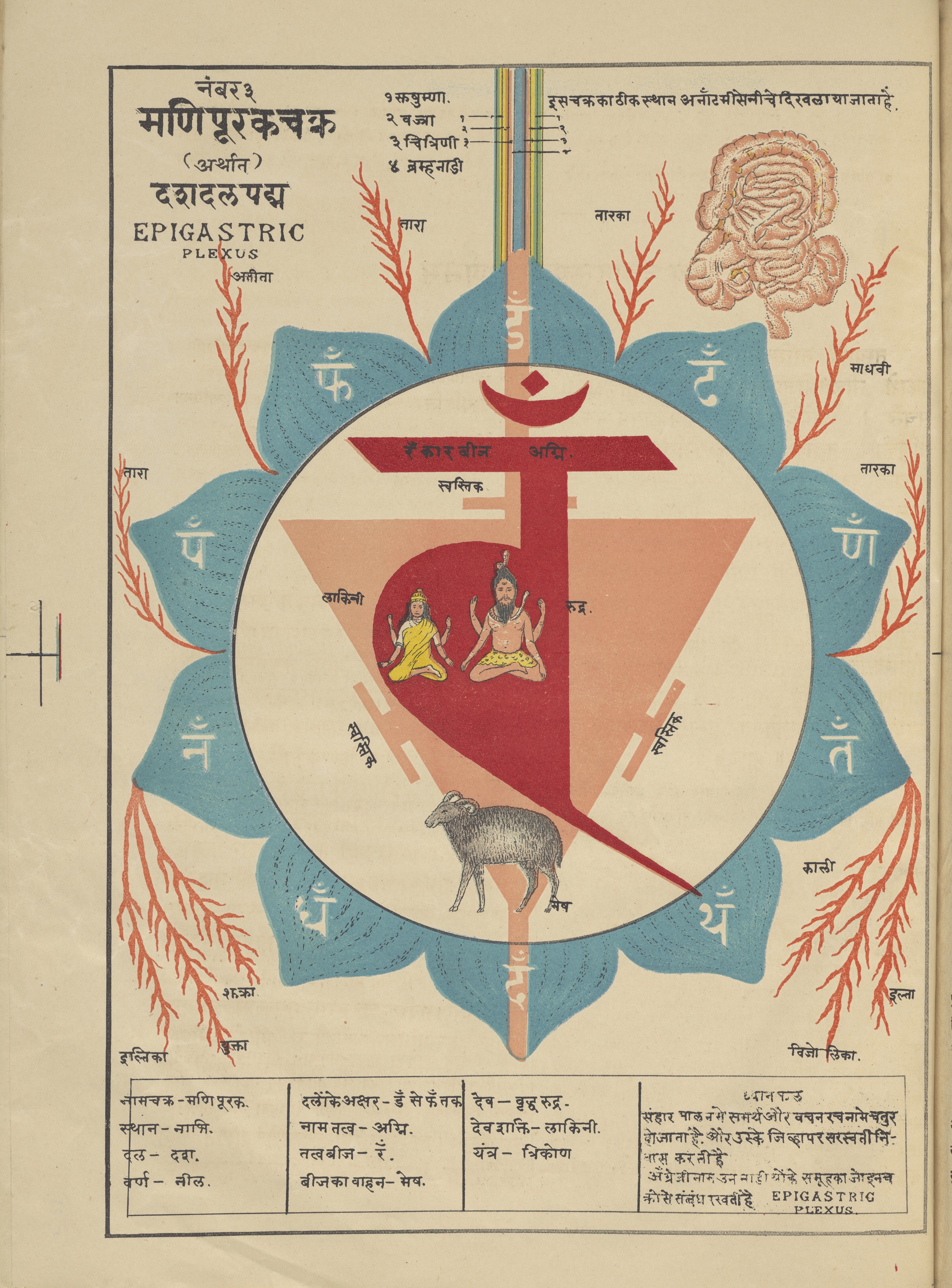

Image: Colour plates in Hamsasvarupa Maharaj, Satcakranirupanacitra, Trikutivilas Press, Muzaffarpur, 1903. Wellcome Library, London.

Nilofar: Is there a chronology to the exhibition design?

Ratan: I am less interested in when the object was made or its historical timeline, and more interested in the how and why. The exhibition is not a chronological account of the evolution of the medical practice in India. If you wanted to get that from the show, you could, because we do provide information about the origins of Ayurveda, we say something about the contact between Indian healing practices and the medical practices and rituals from abroad. In that way, this show is quite open to interpretation.

Two examples: One of the great historical conundrums in understanding medicine in India is that there are hundreds and thousands of manuscripts across the country, in various forms, ancient and modern. India has this ancient tradition of producing medical manuscripts, what’s missing is drawings and diagrams. The medical texts are just that – endless lines of Sanskrit or other languages, with no illustration. There’s no historical tradition of medical illustration in India. Under the Muslim rule, Unani’s influence circulated in India, textbooks like the Tasrih-i-Mansuri, for example.

There’s an 18th century Gujarati illustration, which shows the circulatory system, the arteries based on the Tasrih-i-Mansuri, but with an Hindu overlay of Chakras. That syncretic tradition is very powerful in India. It’s a Hindu medical text, but it uses its medical illustrations from another source. And this continues through history. There’s also contact with Western anatomical models. An illustration from a book, which tries to equate the Chakras with Western anatomy model. This can be found in the section called The Clinic.

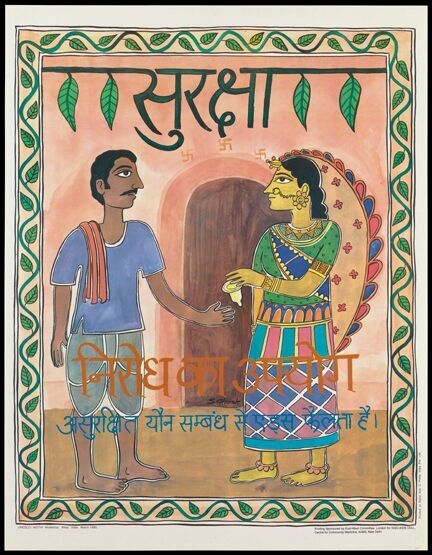

Image: Advertisement for Nirodh condoms to prevent AIDS, UNESCO- All India Institutes of Medical Sciences. Color lithograph, 1999. Wellcome Library, London.

Nilofar: What’s the story behind the title of the exhibition?

Ratan: Tabiyat is a beautiful, subtle, interesting word and it comes from Unani medicine. It entered Hindi from Urdu and Urdu from Persian and Persian from Arabic. In Arabic, the term tabiyat just means the nature of things. By the time it gets into Persian, it means health, but in the Muslim understanding of health, which is that the body and the mind have an internal resilience. There is no such thing as an external cure or medical intervention. What you are doing is basically encouraging the body to heal itself, because only Allah has the power to heal. That’s the origin of the word, but this resonates very much with the Ayurvedic understanding with how the body works. There’s very little conflict between Ayurveda and Unani, they blend very beautifully. They do practice different systems and show different cultural affiliations, but conceptually, they are pretty close.

Tabiyat is a very common word in India for both physical and psychological health. And it’s an all encompassing health. When you ask the question, “Aapki tabiyat kaisi hain?” what you are enquiring about is not just the person’s physical well-being, but how is everything is going on in your life, how is your disposition, your mental well-being. I wanted the word to be resonant.

Image: Jaipur artificial limbs for Adult male, adult female and child, 2015. Acquired for Wellcome Collection, London, courtesy of Bhagwan Mahavir Viklang Sahyata Samiti.

Nilofar: Does the exhibition highlight any mythologies related to health, in terms of stories and origin myths?

Ratan: We reference both legends and ancient histories, if not specific mythologies. For instance, we highlight the mythology of Dhanvantri. In another section, we reference the Indus Valley Civilization and highlight the lota – we talk about that in the context of hygiene and ritual purification, which is very connected in India.

It’s important to understand that the subject is way bigger than the exhibition. The art of curating is selecting and even though we have packed a lot of historical objects into the exhibition, there will be a section of the audience who might find that Tabiyat is not comprehensive in its survey in terms of histories and chronologies.

We have done something provocative, something innovative through showcasing amazing objects and we are making people think again about their lives.

Image: Amrutanjan Pain Balm box, 1950, acquired for Wellcome Collection.

Nilofar: What about illnesses or injuries, does Tabiyat highlight any specifics?

Ratan: We have a section devoted to medicinal herbs and plants. We are not passing value judgments on any tradition or presenting one system as better or more effective than another. All we are doing is looking, observing, and bringing it all together for the audience. We talk about the life cycle of an individual over several occasions. For example, there’s a story of a Parsi couple, a woman who is dying and the man conducting the fire ceremony, reading from the Parsi scripture. We have showcased this, instead of any specific illness, cure or state of health.

In Mumbai, we have taken an ethnographic approach to Tabiyat where as Kolkata’s show is much more poetic.

In Calcutta, we have a show called “Jeevanchakra” at the Akar Prakar Gallery and it explores healing and health through the prism of contemporary art. We have some of India’s leading contemporary artists looking at the life cycles – those moments in every human life (birth, death) as well as cultural practices related to medicines. For example, we have showcased the practice of the midwife – the dai – so we have a beautiful set of images, Gelatin prints from Gauri Gill to highlight this taken in 2005.

It’s almost like a curatorial point and counterpoint, to use a musical term, to describe how the exhibitions in Mumbai and Kolkata have shaped up. There’s something which you can only really explore through art. So, Latika Gupta, our curator in Kolkata, is the person behind this show. In Mumbai, we have taken an ethnographic approach to Tabiyat where as Kolkata’s show is much more poetic.

Image: Neem Margosa, colored line engraving, 1683, for Hortus Indicus Malabaricus, Hendrik Adriaan van Rheede, 1688. Wellcome Library London.

Nilofar: Do you see some kind of contradictions or dilemmas in how Indians approach health and well-being?

Ratan: That’s exactly what the show highlights, things blend, merge into each other and this is how it’s always been. The boundaries in the show are not generic locations and in fact the way the show is designed, physically, these are not closed room. Things that could have been placed in the home, can be found in the clinic, and things that you would see on the Street would also be found in the Shrine. It’s all inter-connected in India.

I hope the physical design of the show comes through and reflects the fluidity, the porosity of the boundaries between the four sections. What I also want people to take note is that there are many different systems and practices highlighted by Tabiyat, however, there’s a fundamental recurring difference between analytical models such as Western medicine, Ayurveda and Unani, on one hand, and an approach to health that’s more spiritually oriented, on the other hand.

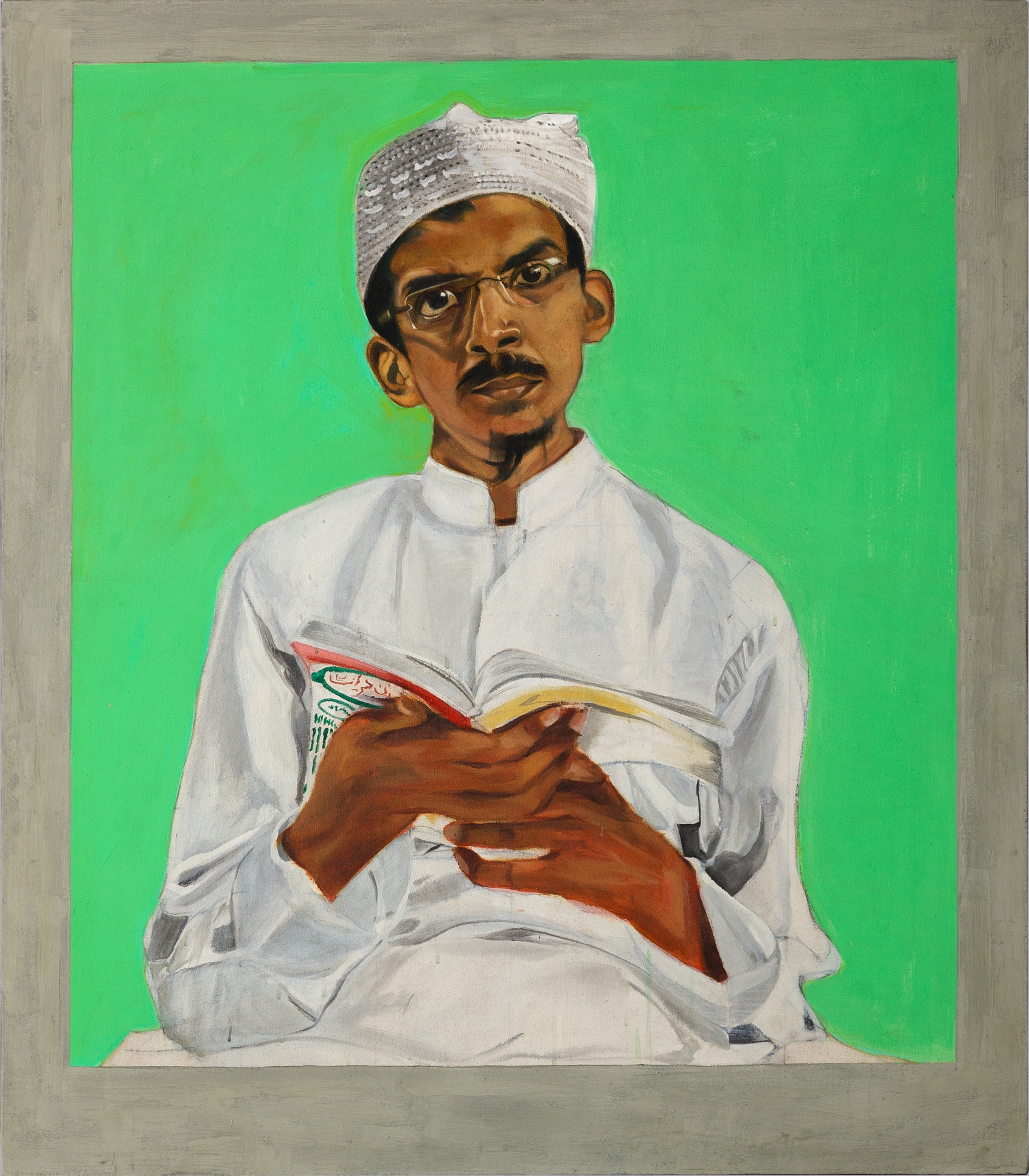

Image: Mahindra Vartak, Portrait of Abdul Azim Kazi, Faith Healer. Plastic paint on canvas, 2015. Acquired for Wellcome Collection, London.

Nilofar: How would you describe your experience setting up this exhibition?

Ratan: It has been a tough job, yes, but equally challenging and rewarding to work on this exhibition, over the last three years. We have focused on high production values, in terms of signage, lighting and design. Everything in the space has been set up from scratch, carefully considered. Tabiyat is a thoughtful show, but it’s not very intellectual in nature. It’s accessible, and not something that would intimidate anyone. I hope people will take that away from the show that it’s about them.

For more information on Medicine Corner, visit: http://medicinecorner.in.

Recent Comments