Dr. Alexandra Woodall, an experienced museum and gallery interpretation practitioner, researcher, teacher and consultant, shares with us her project Things Unbound.

Introduction

This blog post explores one aspect of the Things Unbound project, a partnership funded by UKIERI and the British Academy (2014-2017), between the School of Museum Studies at the University of Leicester, UK (led by Professor Sandra Dudley) and the National Museum Institute in New Delhi, India (led by Professor Manvi Seth). The research took place in sites including: in India at Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum, or City Palace Museum in Jaipur, Rajasthan, and Thiksay Monastery in Ladakh; and in the UK at Ely Cathedral in Cambridgeshire, and Harborough Museum at Market Harborough in Leicestershire.

The aim of the project was to ask what it is that objects do at the moment of encounter between person and thing – and indeed whether it is even possible to research this question. What is it that makes us say ‘wow’ in awe, surprise, or amazement, when we are confronted with a thing of beauty, or intrigue, of immensity, or intimacy? Is it possible to say what it is, and how might we explore this from the object’s point of view?

The research was undertaken with partners (including PhD students, independent researchers, museum staff, academics), working across different cultural and museum contexts – from the UK and from India – and with different areas of expertise – a true intercultural dialogue. A further question thus arose around the benefits and challenges of this collaborative approach for museum practice and object research. What did we all learn from our colleagues and partners who had such diverse experiences and backgrounds, who were working student alongside academic alongside museum professional, all as equals?

Detail of City Palace Museum, Jaipur (photo by Alexandra Woodall)

Methods

The qualitative research we undertook in the very distinct museums and religious sites was organic and open-ended. It included observation, interview, participant workshops, object handling and audience questionnaires. In each case, we were exploring the visitor’s engagement with particular objects, and whether we could tell what it might be about those particular objects – or any object, for that matter – that made people respond, and whether there were characteristics of those objects which were giving way to particular responses. Data gathered by the large research team was also organic and open-ended, depending on each researcher’s own preference and learning style. A plethora of data by over 30 researchers includes field notes, sketches and drawings on iPads, photographs, conversations and sound recordings.

Alongside the gathering of data in different settings, several workshops for researchers and colleagues provided rich environments for discussion, at times opened up to people not engaged with the project. In addition, the project also enabled new ways of working to be introduced at some of the sites in which we were based, as a form of action-based research.

In this blog post (the first of two or more?), I focus on just one aspect of one of the project: a particular object handling workshop used as a way to gain and demonstrate new insight into object-centric practice and theory, particularly as experienced with the team working on the project at City Palace Museum in Jaipur.

Handling a small frog (photo by Alexandra Woodall)

Handling objects

In the UK, handling objects within museum contexts has a long history and is a regular feature of many museums’ public programmes. Museums often have ‘handling stations’ for audiences to engage with objects through touch (be they real accessioned objects from the collection, replicas, 3D printed versions or objects that have a similar texture, for example). My own professional museum experience (as an education practitioner and as a researcher) has involved exploring object handling for the past 15 years or so, in a variety of contexts. Often such object handling programmes are run by members of the learning and engagement team in a museum, or by volunteers, or sometimes by staff within the visitor services or ‘front of house’ teams.

I am particularly interested in what we can learn from a direct experience with an object through touch, that we cannot learn just by seeing it in a glass case, or merely by reading a label. How can this direct experience engage with our emotions, or with our bodies, in a way that the ‘dead’ object in a glass case cannot? Museum objects have largely been stripped from their original contexts: largely they were not made to be exhibited in museums. They were made to be played with, eaten from, used for worship and ritual, for wearing, making music and so on. The museum strips them of the life they once had.

The capacity that an object has for engaging with our emotions, our senses, our memories and our imaginations, is not something that will often be written about in a traditional text panel or label. The writing we come across in a museum usually focuses on the contextual background of an object: what it is, who made it, what it is made from, how big it is, what it is for, what the historical situation was at the time and so on. But what happens if we strip an object of all this context? What happens if we just encounter it as a thing? What happens if we prioritise our own immediate, visceral, embodied, imagined, experience, often shaded with memories and our own life histories and previous experiences?

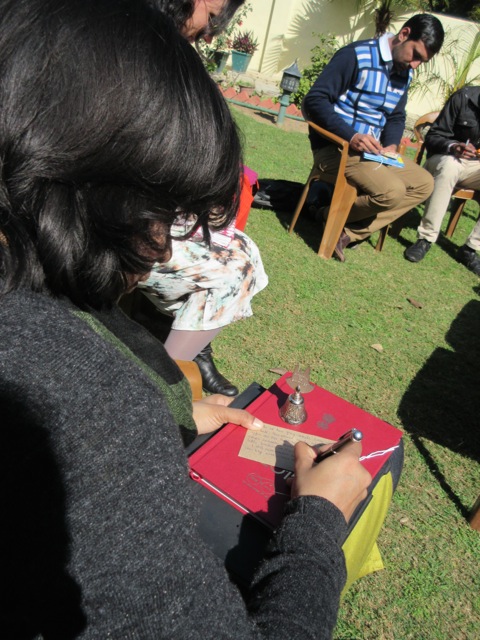

Writing object label (silver bell) (photo by Alexandra Woodall)

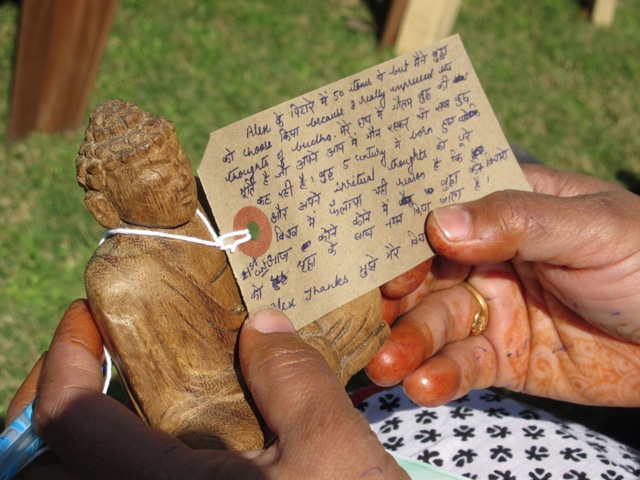

Object label (wooden Buddha) (photo by Alexandra Woodall)

Creative workshop

On Thursday 5 February 2015, the project team held a workshop sitting in the sun in a garden of the University of Rajasthan’s guest accommodation. We had undertaken almost a week of observation and encounter at the City Palace Museum prior to this and had exchanged ideas and questions throughout the week. This workshop was a chance for us to sit back and reflect, and plan the following week. 14 researchers were present and I was facilitating the session and ensuing discussion. I had brought with me from the UK a box of objects. It is not just a rectangular cardboard box: rather, a bright green hexagon, it unravels beautifully to reveal a series of small hidden compartments. Each of which I had filled with a ‘random’ object, with no context, no information, no label. The aim of my workshop was to get people to talk about objects without the barrier of needing to know the context of the thing. Things have a way of drawing us to them, and I wanted to use my box to explore whether and how this might be the case.

Part of the excitement lies in the performance of unravelling the box. How does the box open? What might be inside? Conversations were ripe. On opening, participants could see the array of extraordinary things before them. Each person was then invited to choose an object from the box. They were given no instruction other than to choose a thing. Each participant took delight in choosing an object, carefully.

Object box (photo by Alexandra Woodall)

But why had they chosen the particular objects? Having discussed an initial object, participants were then invited to either stick with that one or pick another that resonated with them. They were given a luggage label on which to write their reasons for choosing that object. Or perhaps why the object had chosen them. On sharing these, and hearing colleagues’ reasons for choosing objects, they were as varied as the objects themselves. Some objects were reminders, heralding a past now long gone, or a memory confined to the back of the mind. Others were beautiful shapes, made from exquisite materials, or simply too beautiful to ignore. Others became new things, stories were made up: it could be an object for doing this, that or the other. Participants were captivated. Some were moved to tears. Others were drawn into conversations never had before. And so, through this very simple first workshop, perhaps something that a familiar – or in many cases an unfamiliar – object does was indeed revealed. Perhaps one small element of the research project – that objects do something – was made manifest through this workshop in the sun. Perhaps we learnt as much about our fellow researchers as we did about the potentialities within the objects selected.

There is so much to be learnt and developed in museum practice about the imaginative, creative, emotional and sensory potential of objects. The next blog will explore a concrete example of shifts in practice and ways of working that happened as a result of this object-based research.

Dr Alexandra Woodall (Norwich, UK) is an experienced museum and gallery interpretation practitioner, researcher, teacher and consultant. She is particularly interested in how people encounter objects. Until recently she was Head of Learning at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (University of East Anglia, UK), and has previously worked for institutions including Royal Armouries, Manchester Art Gallery, Museums Sheffield and Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. www.alexwoodall.co.uk @alexwoodall

Dr Alexandra Woodall (Norwich, UK) is an experienced museum and gallery interpretation practitioner, researcher, teacher and consultant. She is particularly interested in how people encounter objects. Until recently she was Head of Learning at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (University of East Anglia, UK), and has previously worked for institutions including Royal Armouries, Manchester Art Gallery, Museums Sheffield and Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge. www.alexwoodall.co.uk @alexwoodall

ReReeti works with museums, galleries and heritage sites across India to plan strategies, design systems and implement programmes to increase audience engagement and institutional/ company visibility. Email us at info@rereeti.org for a free consultation or to collaborate on an upcoming exhibition.

Recent Comments