Last month, I attended a day-long, state–level, arts education seminar organized by the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA). This seminar, part of the Bangalore-based organization’s Kali Kalisu (it means, learn and teach in Kananda) initiative, focused on arts-based training for teachers from government schools in Karnataka.

So far, approximately 500 government school teachers, across seven districts, were given an orientation to the world of arts through past IFA grantees. The five art forms that are part of this initiative include movement arts, theatre, music, puppetry, and the visual arts. While many of us agree on incorporating arts into education, few modules are able to systematically blend arts and ‘formal learning’ into ‘impactful learning’.

This seminar was important for Rereeti on several counts. Museums are repositories of the world’s civilization and culture as well as being spaces of learning, exploration and platforms to impact knowledge. While schools and cultural organizations leverage arts as a medium of communication, how often do we step back and evaluate the impact of this education? As curators, how often do we asses visitors interaction with exhibits? Do we question the relevance of our methods? I was hoping to engage with other professionals and cultural practitioners and open a dialogue around these questions.

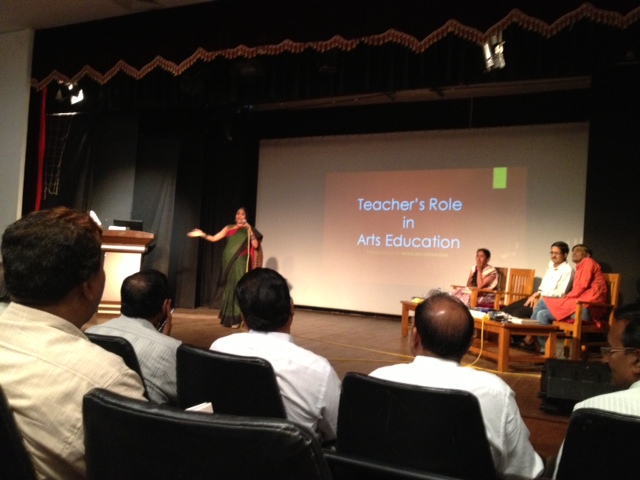

The first half of the seminar saw presentations and discussions focusing on the teacher’s role in arts education. The key takeaways were that being a teacher is more than just fulfilling the functional aspect of using your academic skills, gaining experience in the classroom or imparting knowledge through updated learning theories. Teachers need to balance their personal growth along with their teaching, which requires that they learn about themselves. In this way, they can transform their relations with students by striking a balance in their educational activities.

The last point is highly relevant for museum professionals. As curators, the shows we curate, design and exhibit do not come into being in a vacuum. The exhibits stand for both, the organizations that we represent as well as the cultural milieu that we belong to. The exhibitions that we curate are, inevitably, reflections of our personal narratives, and are shaped by our academic learning, knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes. All these influences what we highlight or leave out in an exhibit, and in turn, what visitors and our audience experience. Just like teachers, curators also need to be sensitive in their outreach activities.

The highlight of the seminar was a skit performed by students of a government school in Gulbarga. The kids narrated the importance of a balanced diet using local theatre forms and techniques. The skit addressed local myths pertaining to health and belief in superstitions as well. It integrated the school syllabus; local art forms and the use of MI (multiply intelligence).

Performance-based interventions are not restricted to academic settings and can be staged in other spaces including the street, heritage sites and museums. A few years ago, the Center for Public History at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology, Bengaluru staged a play on Tipu Sultan. It was performed against the Bangalore Fort acting as backdrop. I still remember the sense of wonder and nostalgia the play induced. It was like going back in time and immersing oneself in living history.

Long after the performers took a bow, the audience were seen discussing the historical significance of what was staged and sharing their own snippets of information with each other. Isn’t that the whole point of education – to encourage informed conversations among your students?

If your museum has staged any such interventions we would be happy to hear about it. Get in touch with Rereeti and we will feature your story.

About the Author

Tejshvi Jain is the founding director of Rereeti and worked at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Bangalore prior to setting up this non-profit organization.

Tejshvi Jain is the founding director of Rereeti and worked at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Bangalore prior to setting up this non-profit organization.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks