In part 1 of her post on ‘Writing Text for Museums,’ Lucy Harland took us through the guiding principles that curators should keep in mind while drafting signage. In part 2 of this post, the author delves into the intricacies of crafting text for various audiences.

If you are going to deliver a presentation or speech, you would start by thinking about who you are speaking to. If you are writing a museum label, you should start by thinking about who is going to read it. Are your visitors local people or more likely to be overseas tourists? Does your museum attract families with young children or students with a high level of specialist knowledge? Writing for each of these audiences will be different.

Then it’s important to decide what you are going to say by identifying the key points that you want to make. Most exhibition labels in the UK are quite short – 30 or 50 words to explain one object at most, and 100-150 words for explanatory texts on the wall. In this limited space, it’s best if you have a clear idea about the ideas or knowledge you wish to convey. Think about the exhibition as a whole – what is the broad theme of the gallery or this specific part of the display? How does a particular object help tell that story? There are usually too many things to say but it’s much easier to write if you have identified your key messages first.

For objects, I start with the idea that the best labels encourage our visitors to look more closely at the object itself. Try focusing on some really interesting aspect of the object e.g. an interesting detail, an unusual feature, information about the person who owned it or how the object made an impact on its owners or users.

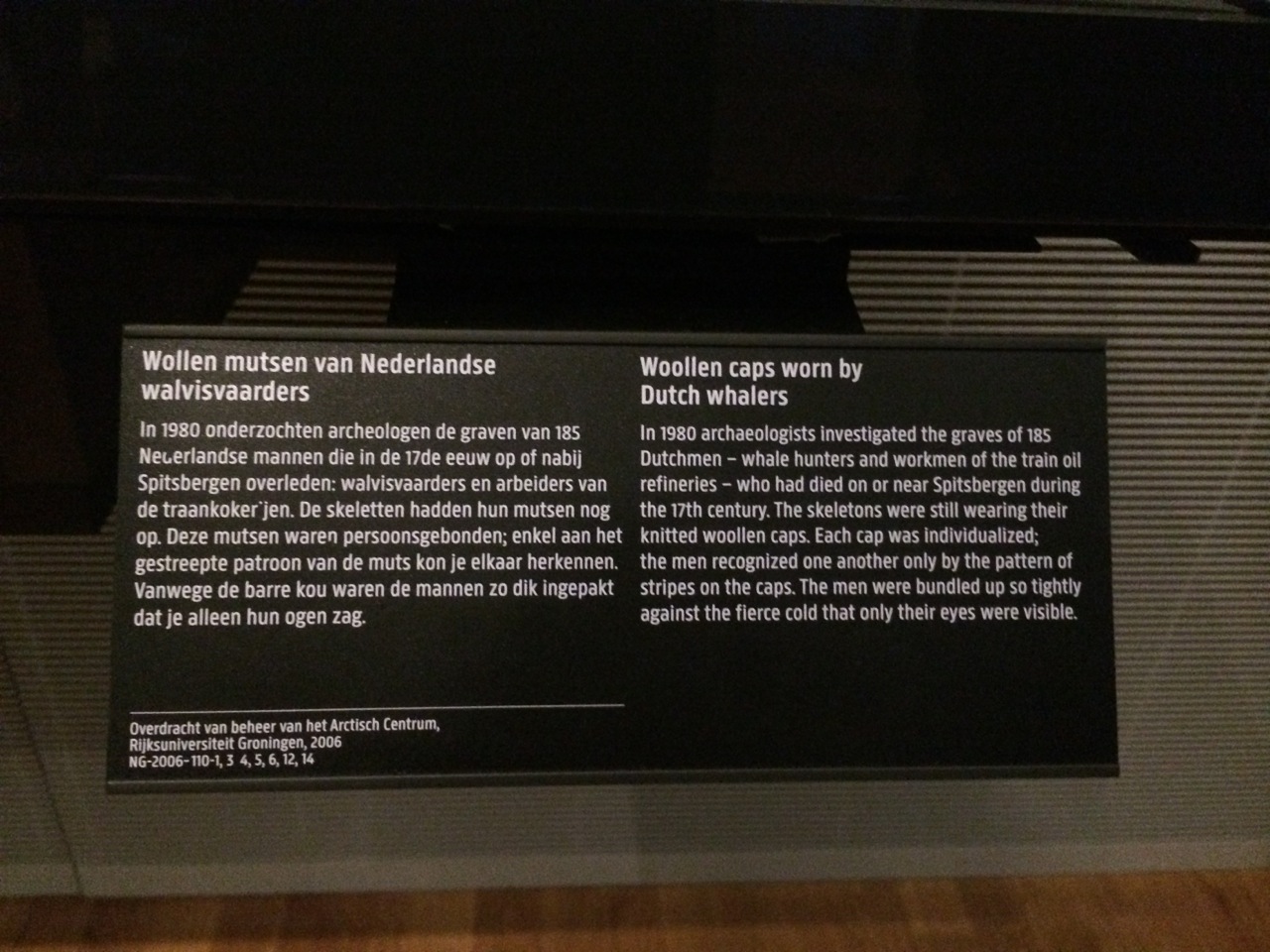

This example at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam contains a really interesting story that evokes the lives of sailors working on ships in the freezing cold seas of Northern Europe. These apparently simple objects are brought to life by the writer describing where, how and why the hats were worn, and how they were discovered.

For longer texts, think about which ideas and themes will give useful context to your objects. Can you talk about the person who made or used an object, and give a sense of their life and interests? Can you explain an idea or an historical period by describing a key moment that changed the course of events?

Finally, you need to start writing! When a task is challenging, it can be easy to think of other jobs to do first but the writing will get better and easier, the more you practice.

Think about the people who will read the text – what do they know already? Be careful about assuming they have the same specialist knowledge as you. Make sure you are helping them to understand. Reflect on what you would say if you were explaining this object in person as part of a tour and use the same language – don’t be afraid to show that you find this object fascinating!

Then keep writing, checking and, most importantly, showing your text to other people, especially the kinds of people who visit your museum. If you are trying a new approach, why not make some temporary labels and ask your visitors what they think? Show your text to a colleague, perhaps one who doesn’t share your expertise or who works with your visitors as a guide or educator, and ask them for an honest opinion. Most importantly, remember that you probably won’t get your text right the first time. Good luck!

About the Author

Lucy Harland is a museum interpretation consultant working with a range of UK and international clients. Lucy has a particular expertise in exhibition planning and museum text writing and editing. She was formerly a museum curator and a BBC radio producer. Follow her on Twitter.

Lucy Harland is a museum interpretation consultant working with a range of UK and international clients. Lucy has a particular expertise in exhibition planning and museum text writing and editing. She was formerly a museum curator and a BBC radio producer. Follow her on Twitter.

Thank to ReReeti so much to show and teach so many great contents about the museum’s world, we really appreciate it. Our best regards.